As I’ve been experiencing a resurgence in my writing, I’ve been thinking quite a lot about the creative process. How do ideas come into being? How are stories, poems, sketches, and songs created? Is it better to schedule in consistent, daily times for writing or is it better to write when the ideas move you?

The Idea

Some poems and stories flow from my brain as whole pieces, like Athena being born from Zeus’ head. Last year, I wrote a complete science fiction short story in my mind as I was about to fall asleep. Ideally I’d have penned it that night or the next morning, but I’m only pulling it out my brain now. Other ideas start out as a tiny spark: a scene, an image, a line of dialogue, a collection of notes, or a writing prompt. These ideas tend to need time and even research to flesh out.

Schedules and Word Counts

I’ve learned from a published YA author that it’s taken her vastly different times to complete novels of similar word counts; each one has been unique. Once an idea is on the page, it often takes on a life of its own. She also sets a goal of writing 1,000 words per day. A word count per day (or even week) may be a better way of approaching things for me rather than “I will shut the door and write between 10-12,” as my own creativity tends to ebb and flow. During one writing session at a ski lodge a few weeks ago, I stared out the window and listened to “Wham! Rap” the whole time, tickled by the “DHSS” refrain. On another occasion, the words didn’t come to me try as I might, so I spent the time outlining stories instead, pulling together ideas that had been floating in my head. Reaching a tangible, non-time-bound goal such as “I am finishing/revising this story today” or “I am writing 500 words this afternoon” may be a good middle ground. It’s routine and schedule that I find constraining.

I’ve read a lot about the writing schedules and habits of successful authors: morning vs. evening, outlines vs. no outlines, multiple vs. single projects, schedule vs. none (ok, most writers do tend to have some schedule). A former colleague and part-time writer told me that writing in the morning worked for him even if he wasn’t a morning person, because that way no matter what happened the rest of the day, the writing didn’t get bumped by errands, email, or work. In high school and college, I liked writing in the night, especially between about 10-11 pm because it was quiet and calming with daytime tasks done. I spent this time in different ways: to actualize ideas bursting at the seams, to revise, to gather information, or to read a book. It’s a time that still works for me.

Accountability

Ideas often come to me on a whim, and I try to write them down. But especially with stories, if I don’t treat them like work…I will not execute. I will allow other distractions to get in my way. I have work. I have errands. I have appointments. Also, the words don’t just pour out of me. They tend to be in a fog and I have to put a few down before more will come. What I am starting to see is that for me is that writing begets more writing. It’s a virtuous cycle, much like exercise (or so I hear).

What also works for me is establishing “public” accountability. When I was in the ski lodge, I told my girlfriends: ok, I’m going to go write for an hour now. After I came back, they would ask “How did it go?” and knowing that I needed to answer kept me honest. Sometimes I need a draft, rough as it may be, to work out where I want to or could go. A draft serves as the substrate, something I can react to in order to identify the gaps and think of the connectors. Sometimes I need to walk out the door and down the street before I can draw the rest of the map. Sometimes I need to get lost before I can find my way.

The Sincerest Form of Flattery

I love reading about writers’ processes. I’ve read and heard that writers like Neil Gaiman and Teri Pratchett take a journalistic approach of writing as work, rather than waiting for inspiration to hit. When I was on deadline for my college paper, I generated 500 words, rain or shine. Once in a while, they were good.

Recently, I’ve been getting more into the process of comedy writers like Tina Fey in developing sketches: it’s much more collaborative than writing stories and poems. Their process more closely resembles my professional life, where we have a topic, formulate objective and format, collaborate internally, review with external group leaders, present to a larger group of stakeholders, write and edit drafts, integrate comments, etc. Whether I’m inspired or not, the writing gets done. If I get stuck, I know the time is right to hand it off to a colleague. Inspiration plays a role here too. Some days I’m just not feeling it, so I let it to go a revisit it the next day (deadlines don’t always allow for this luxury).

Over the years I’m finding that writing might be a combination of both inspiration hitting and devoting the time to working on it. The “right brain” seems to be responsible for idea generation and that period of time where I just write and it flows. The “left brain” seems to be responsible for the more analytical tasks involved in planning, outlining, editing, and revising.

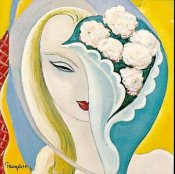

“If Music Be the Food of Love”

For me, music is the crux upon which my creativity rests. I almost cannot write unless I am listening to something I love. I have written so many poems to the beat of songs. Music focuses rather than distracts me, and I derive something unseen from that energy.

Songwriting itself fascinates me. I played piano for seven years, I can still follow sheet music, and I pay a lot of attention to musical arrangements. However, I don’t know the first thing about writing a song. What does that even mean? How do you bring together chords, melody, and lyrics? I had this idea of someone sitting at a piano or with a guitar and writing notes down meticulously on beautiful, blank sheet music stationery. Ok, I think some artists (like Stevie Nicks) create piano demos which then go into production. Others in bands appear to jam. I love what Sting has to say about about starting with an idea around which he can build a whole song, not just the first line because then he has to write the second line. It’s very conceptual and reminds me of how image-based poetry is written. Elton John has had a lifelong partnership with lyricist Bernie Taupin in which Taupin provides a series of lyrics and John writes the melodies-it’s unusual, but it works for them. Yet more unique seem to be those musicians who come to the table with the entire song in their heads, like George Michael or Michael Jackson, who sang each instrument part into a tape recorder. While Michael seemed to have total control over all the parts, Jackson had a more collaborative relationship with producers like Quincy Jones.

Zero songwriting ability aside, I am convinced that I write at all because of that initial love I had for music. Learning piano taught me about rhythm. I started writing poetry the year after I started playing, and perhaps this is no coincidence at all. When I write poetry and stories, I feel the same exhilaration that I used to when playing piano. My fingers flow with joy over the keyboard with flourishes – as though I am playing an instrument.

Quick note on pen/pencil and paper vs. typing: I used to write poems by hand and still do on occasion when I need or crave the tactile element; I started hand-writing stories, but transitioned to computer fairly quickly, as I was too impatient to write prose by hand. I imagine this is partly generational; I also wonder if I viewed the computer keyboard as an appropriate parallel to a piano keyboard. President Obama enjoys writing first drafts long-hand on yellow legal pad. I have toyed with using voice recording to capture ideas but the translation from mind to voice still eludes me.

Ultimately, I only have my best practices to share:

- Write down your ideas: If you have an unreliable memory like me, writing down an idea before it slips from your consciousness can be helpful. You can jot it down on a post-it note, type it into your phone, or scribble into an email or notebook. Just don’t write it on your hand.

- Make time to execute your projects: Time is a finite resource. Others have expounded on tips for how to make time but this is up to you. It may mean sacrificing other tasks that are less important, but only you can decide what those are. Can laundry and dishes wait until morning? Can you skip a social event? Think about what you can let go. Prioritize: this is hard, involves trade-offs, and it cannot be underestimated.

- Experiment with different processes: Do you like to outline? Do you like to draft? Do you need to set goals such as a word count, hours, or a time bloc? If you don’t know, try it all out and see what works and what doesn’t. As you experiment, you will begin to understand the style and process that suits you.

- Develop your writing into a habit: Write every day. Or at least every few days. Make it a habit. Once it becomes one, you’ll want to do it (like exercise, so I’m led to believe). It will be something you look forward to doing. Yes, it’s work, but work you want, need and love, right?

- Give yourself a break: Nobody’s a machine. Find out what works for you during the process and to reset you during down times. Music, tea, reading. Sometimes, it’s about the magic that happens in between as your unconscious sorts it all out (in bed, in the shower, on the metro).

Or just toss all these notions out the window and just write!